Executive Summary

An automated irrigation system refers to the operation of the system with no or just a minimum of manual intervention beside the surveillance. Almost every system (drip, sprinkler, surface) can be automated with help of timers, sensors or computers or mechanical appliances. It makes the irrigation process more efficient and workers can concentrate on other important farming tasks. On the other hand, such a system can be expensive and very complex in its design and may needs experts to plan and implement it.

Advantages

| In | Out |

|---|---|

| Freshwater, Fertigation Water, Treated Water, Energy | Food Products |

Introduction

An automation of irrigation systems has several positive effects. Once installed, the water distribution on fields or small-scale gardens is easier and does not have to be permanently controlled by an operator. There are several solutions to design automated irrigation systems. Modern big-scale systems allow big areas to be managed by one operator only. Sprinkler, drip or subsurface drip irrigation systems require pumps and some high tech-components and if used for large surfaces skilled operators are also required. Extremely high-tech solutions also exist using GIS and satellites to automatically measure the water needs content of each crop parcel and optimise the irrigation system. But automation of irrigation can sometimes also be done with simple, mechanical appliances: with clay pot or porous capsule irrigation networks or bottle irrigation (see also manual irrigation).

High-Tech Principles

Automation of irrigation systems refers to the operation of the system with no or minimum manual interventions. Irrigation automation is justified where a large irrigated area is divided into small segments called irrigation blocks and segments are irrigated in sequence to match the discharge available from the water source. There are six high-tech automation systems, which are described below.

Time Based System

Irrigation time clock controllers, or timers, are an integral part of an automated irrigation system. A timer is an essential tool to apply water in the necessary quantity at the right time. Timers can lead to an under- or over-irrigation if they are not correctly programmed or the water quantity is calculated incorrectly (CARDENAS-LAILHACAR 2006). Time of operation (irrigation time – hrs per day) is calculated according to volume of water (water requirement – litres per day) required and the average flow rate of water (application rate – litres per hours). A timer starts and stops the irrigation process (RAJAKUMAR et al. 2008 and IDE n.y.).

Volume Based System

The pre-set amount of water can be applied in the field segments by using automatic volume controlled metering valves (RAJAKUMAR et al. 2008). An example for a volume based irrigation method is described in ZELLA et al. (2008).

Open Loop Systems

(Adapted from BOMAN et al. 2006)

In an open loop system, the operator makes the decision on the amount of water to be applied and the timing of the irrigation event. The controller is programmed correspondingly and the water is applied according to the desired schedule. Open loop control systems use either the irrigation duration or a specified applied volume for control purposes. Open loop controllers normally come with a clock that is used to start irrigation. Termination of the irrigation can be based on a pre-set time or may be based on a specified volume of water passing through a flow meter.

Closed Loop Systems

(Adapted from BOMAN et al. 2006)

In closed loop systems, the operator develops a general control strategy. Once the general strategy is defined, the control system takes over and makes detailed decisions on when to apply water and how much water to apply. This type of system requires feedback from one or more sensors. Irrigation decisions are made and actions are carried out based on data from sensors. In this type of system, the feedback and control of the system are done continuously. Closed loop controllers require data acquisition of environmental parameters (such as soil moisture, temperature, radiation, wind-speed, etc) as well as system parameters (pressure, flow, etc.).

Real Time Feedback System

With this application irrigation is based on actual dynamic demands of the plant itself; the plant root zone is effectively reflecting all environmental factors acting on the plant. Operating within controlled parameters, the plant itself determines the degree of irrigation required. Various sensors, tensiometers, relative humidity sensors, rain sensors, temperature sensors etc. control the irrigation scheduling. These sensors provide feedback to the controller to control its operation (RAJAKUMAR et al. 2008).

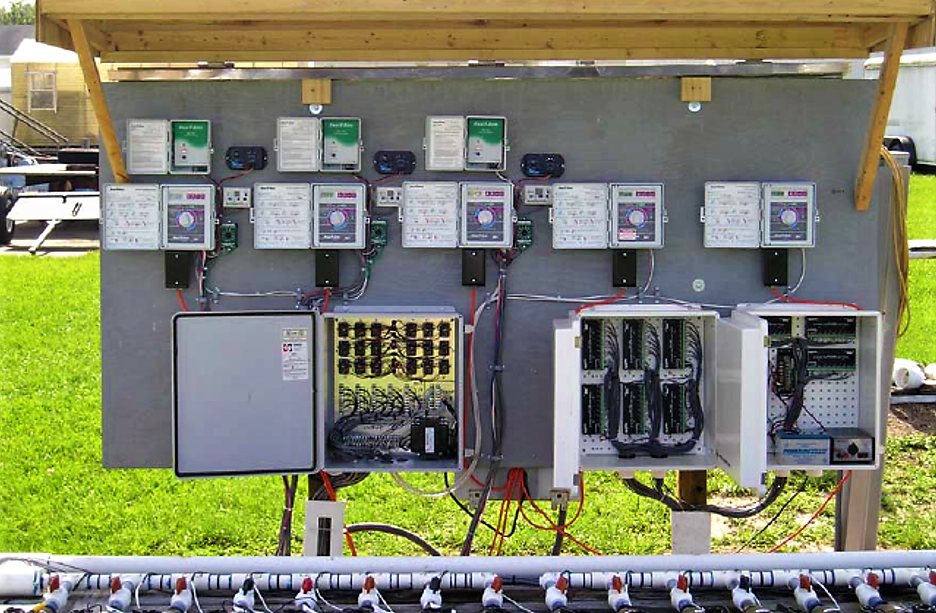

Computer Based Irrigation Control Systems

A computer-based control system consists of a combination of hardware and software that acts as a supervisor with the purpose of managing irrigation and other related practices such as fertigation and maintenance. Generally, the computer-based control systems used to manage irrigation systems (e.g. drip irrigation systems) can be divided into two categories: interactive systems and fully automatic systems. Read more about it in RAJAKUMAR et al. (2008).

Besides these high-tech solutions there are also effective methods without any energy supply. Optimising a system mechanically with the help of gravity can automate an irrigation process. Examples are the small-scale and self-made drip irrigation systems described here or the systems described below.

Low-Tech Principles

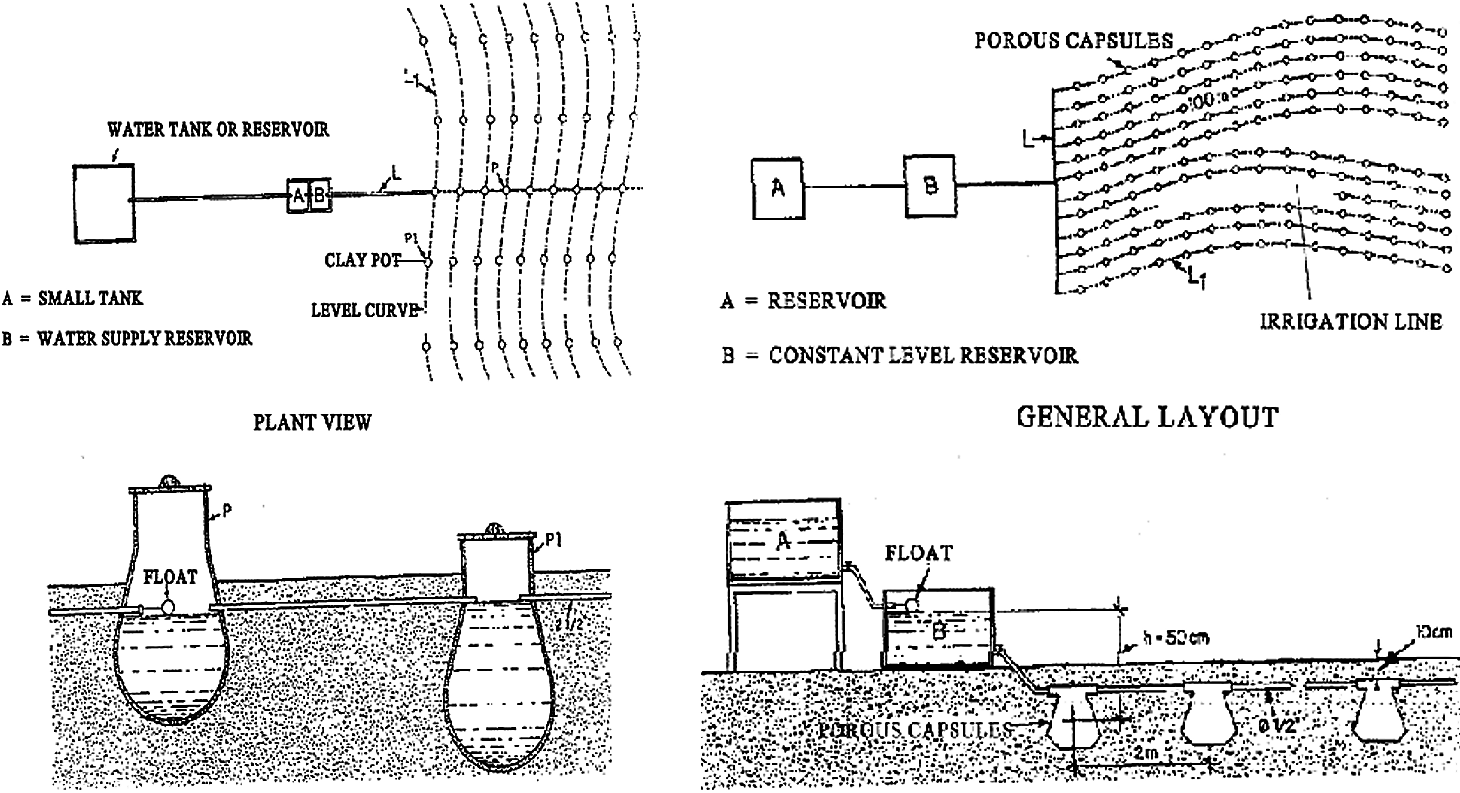

Clay Pot and Porous Capsule Irrigation Network

(Adapted from UNEP 1998)

This old system has been modernised and reapplied in water scarce areas. The technology consists of using clay pots and porous capsules (see also pitcher irrigation) to improve irrigation practices by increasing storage and improving the distribution of water in the soil. This low-volume irrigation technology is based on storing and distributing water to the soil, using clay pots and porous capsules interconnected by plastic piping. A constant-level reservoir is used to maintain a steady hydrostatic pressure. Clay pots are open at the top and are usually fired in home furnaces after being fabricated from locally obtained clay or clay mixed with sand. The pots, usually conical in shape and with a capacity of 10 to 12 litres, are partially buried in the soil with only the top poking out. Distribution is done by plastic (PVC) piping to ensure a fairly uniform permeability and porosity. Maintaining a constant level in the storage reservoir regulates hydrostatic pressure.

A similar system, tested in Mexico and Brazil, uses smaller, closed containers, or porous capsules, completely buried in the soil. These containers distribute the water either by suction and capillary action within the soil, or by external pressure provided by a constant-level reservoir (as in the previous system). Each capsule normally has two openings to permit connection of the plastic (PVC) piping which interconnects the capsules. The capacity of these capsules ranges between 7 and 15 litres, and the storage tanks supplying the system are elevated 1 or 2 m above the soil surface. The capsules are buried in a line 2 meters apart, at least 10 cm under the top layer of the soil. The number of pots or capsules used is a function of the area of cultivation, soil conditions, climate, and pot size. Up to 800 pots/ha were installed in Brazil.

Automatic Surge Flow and Gravitational Tank Irrigation System

This is an intermittent gravity-flow irrigation system. It has been used almost exclusively for small-scale agriculture and domestic gardening. Prior to the development of this technology, electronically controlled valves were used to produce intermittent water flows for irrigation. These valves are expensive and require some technical training to operate. The siphon replaces these valves with a device that would be more cost-effective and easier to operate and maintain with a minimum consumption of energy. The system consists of a storage tank equipped with one or more siphons (see figure below) (UNEP 1998). The water in the tank flows to the field because of the siphon effect. As soon as the tank is empty, the flow stops. For the next irrigation process, the tank has to be filled-up to restart the siphon effect again. To learn more about possible siphon designs see VORTECH (2009).

Another system that produces similar results is the use of a storage tank with a bottom discharge. It is equipped with a floater, which allows the cyclical opening and closing of a gate at the bottom of the tank. In effect, the operation of the floater is similar to the mechanism in the storage tank of a toilet flushing system. The materials normally used in the construction of the water storage tanks are gravel and cement, reinforced concrete or plastic. The siphons are usually built of a flexible plastic material; PVC is not recommended (UNEP 1998).

Cost Considerations

Costs highly depend on the applied system. It varies from very cheap (e.g. timer) to very expensive systems, which includes research on soil quality and technical material.

Operation and Maintenance

Automatic irrigation systems need to be operated by skilled labourers and maintained frequently. Malfunctions of sensors and valves have to be avoided at all cost and common repair work (e.g. leaches, blockages) has to be considered as well.

At a Glance

| Working Principle | The irrigation system is either mechanically or electronically automated. This allows for very efficient irrigation. |

| Capacity/Adequacy | Every irrigation system can be automated rendering it more efficient. |

| Performance | High |

| Costs | Depends on the size of the irrigation system and the degree of automation. From very small- (timer which activates the valve) to big-scale systems (e.g. real time feedback system). |

| Self-help Compatibility | Expert design is required for commercial systems. A small-scale system (e.g. time based) can be installed by the farmer. |

| O&M | These systems need to be operated by skilled labourers and maintained frequently. They also require thorough surveillance. The proper functioning of sensors and valves as well as common repair work (e.g. leaches, blockages) has to be considered. |

| Reliability | Very reliable if operated and maintained well. |

| Main strength | High water application efficiency. |

| Main weakness | Complex designs can be expensive. |

Almost every irrigation system can be automated. It makes sense in every region of the world as it saves time and water. Furthermore, high-tech designs allow for very efficient irrigation i.e. metering the water volumes more precisely. Once the system is optimised, labourers do not have to worry about the irrigation process and can concentrate on more important tasks.